by Rich Baer, Master Rosarian and Botanist, Portland Rose Society

This article was originally published in The Portland Rose Chatter, February 2021.

As a person who grew up as a plant person and obtaining a plant education including advanced degrees in Botany, I am very attuned to the lingo of the plant world. As with any specialty there are a lot of words that are unique to the field and are often misused. As long as it does not lead to any communication problems, it really does not matter. If roses have thorns or not is not a major problem, because we all understand what roses do have and what exactly we call them, (the correct word for them is prickles), causes no problems.

One little phrase for describing the rose classes does however bother me and I have spoken about it a number of times and that is referencing roses that have one row of petals as being single petaled roses. This problem came from exhibiting roses. One rose in a vase for entry purposes is referred to as a single rose. So, then what do we call a rose that has four to eight petals in one row around the bloom? To differentiate it from one rose in a vase it began to be referred to as a single petaled rose. The picture to the right is what a collection of four single petaled roses would look like. In nature there are no single petaled roses. The minimum number of petals in any rose currently known is four which is the number of petals in Rosa Omeiensis Pteracantha, also called the wingthorn rose. This is the rose with the very large red prickles which is the reason those who grow it do so. For the sake of exhibition the American Rose Society has defined a single rose as one which has between 4 and 8 petals. Personally, I find single roses to be very attractive and probably have as many as 20 or more of them in my rose collection.

Every day that we do go out into our rose gardens we observe the roses growing. I believe that this year (2020) they have done exceedingly well with great vigor and many many blooms. However, do we ever look at that rose growth very carefully and up close? As a botanist I am always watching to see exactly what my roses are doing so that I can gain more appreciation for what I am seeing. A number of visitors to my garden this year have commented on how tall my roses are. I usually reply that because I look at them more as a garden, how high the flowers are is not a concern. The picture on the right represents a typical new stem growing from an old stem at the point that the last deadheading was done.

The stem typically grows rather rapidly, producing leaves at intervals from nodes along the stem as it grows. At each of these nodes, at the base of the leaf is a vegetative bud. At this point in its growth you will never see any side shoots developing from this shoot. If you look closely at a stem you can find the tiny buds at the very base of each leaf located along the stem. At the very tip of this stem there are thousands of cells called the apical meristem. These cells divide into non differentiated cells. That is, they are not leaf cells or stem cells. They will eventually become specific cells that will grow into leaves and other tissues along the stem as time passes. But back at the tip of the stem, the meristem cells continue to divide and at the same time they are producing new cells, they are also producing auxin, the most well know plant hormone. This auxin travels down the stem and its presence prevents any of the new buds that have formed at the nodes from growing. This is the reason that you rarely see side shoots on the newly developing canes. At a point in time that is determined by several factors, including environment and hormones the vegetative stem will become reproductive. The meristem cells produce cells that become the forerunners of a flower. Once the flower bud begins to grow it occupies the tip of the stem and there are no longer any meristem cells. All of the new parts have been produced by the meristem cells, the stem and foliage beneath them and the growing flower bud above them. The picture “reproductive stem” shows the existence of the flower bud from the tip of the stem. When you can first see the tiny bud it is the first time you will notice that the stem is about to bloom, but the production of this new bud has been going one for quite a while. With the disappearance of the meristem cells there is also no more production of auxin at the tip of the stem. The reduction in the concentration of auxin in the stem allows the previously inhibited buds near the tip of the stem to begin growing. Depending upon the variety of rose, the number of these stems which will begin growing can vary. You probably know that part of the definition of the hybrid tea rose is one that grows with one flower per stem. Without disbudding, you rarely get just one bud and flower per stem, you usually get more than one bud at the tip of the stem.

The picture left represents what a single bloom looks like. There is the developing flower which is attached to the plant by a stem. However, this attaching piece is not a stem but varies from any other stem on the plant in several ways. This structure also has its own unique name and is called the “peduncle”. The most obvious difference you can see by looking at it is that it has no nodes. No leaves have developed along its length. It does however originate at a leaf node, much as any other stem on the rose plant. If you deadhead by snapping off the dead flowers this peduncle usually cleanly snaps off at its origin when you push it over. If you do remove dead flowers this way, just grasp the peduncle between thumb and forefinger and bend to the left or right. After it breaks off, look at the tip of the stem left on the rose bush and you will see at its very end a leaf. It may be a regular leaf that you will recognize as a leaf, or it may be just a little green fold which does not look like a leaf but it is. If you tried to break a rose stem you will not find that it will cleanly break away from the plant as does the peduncle. Sometimes the peduncle will not snap off cleanly but usually it does. If you have tried deadheading this way you know what I mean.

Almost always after you see a stem become reproductive with a flowering bud at the tip of the stem, you will see additional buds beginning to grow as well. With the absence of auxin to inhibit the growth of the side buds on the rose stem, they often begin to grow. As you can see in the picture on the left we often see side buds beginning to grow from just below the peduncle. In this case, you can see the two nodes, they are at the base of the leaves projecting to the right and left. From the very top node the peduncle of the new bloom is growing, as is one of the side buds. In hybrid tea roses it is often the norm that at least the top two nodes will produce side buds. If you could watch the progress microscopically, what you would see would not be just the emerging of the two side buds. The bud at the base of the leaf would begin to grow just like any bud on the bush. However, it would not grow like a stem for very long. It quickly changes to a reproductive stem and begins to produce a peduncle and bloom. However, the stem often will grow enough before this happens to produce enough normal rose stem to have two or three leaves and thus nodes. So, each of these side buds is produced just like the major bud that is at the tip of the stem. In most cases the buds at the nodes on these side bud stems do not grow, so we have the main bud with an indeterminate number of side buds.

Everything is the same for each of these side buds as it is for the major bud that originally was produced. So we have stems with tiny leaflets at two or three nodes below the peduncle and bloom. The same thing can happen here that happened to the main stem, side buds can begin to grow. They can grow with the same results as we had before.

They will produce very small stems that can have several nodes and tiny leaves and a bud and peduncle on their end. This can lead to a very large spray of roses being produced at the end of the main stem if they are allowed to proceed. This is what happens in the case of many of the floribunda roses and other roses which are grown as landscape roses for color.

The picture above depicts the blooming of one such rose called Greetings, a shrub rose from Jackson and Perkins. The main bud can be seen in the center and is showing color. You can follow the progress of this spray in the stems below. Below the main bud side shoots began to grow and produce stems and buds. Then from those shoots additional side shoots grew and produced buds and there are places in this spray where there is a fourth group of buds being produced. All of the stems and peduncles grow from a node that is marked by the presence of a rudimentary leaf, but a leaf just the same. There are no peduncles which originate from other peduncles and there are no stems that do not originate from other stems.

In this case the original terminal bud will bloom first, and then all of the first wave of side buds will bloom at the same time. Then each additional wave of buds will mature and bloom in sequence. That is why disbudding large sprays can become tedious to the exacting exhibitor. But in the garden, we just let them bloom to produce the great color spots that they can become.

There was a reason for trying to establish how flowers are produced on the ends of rose stems and the importance of the peduncle. The peduncle exists from the bottom of the bloom to the first node from which it came. In this case the node can be easily seen because there is a leaflet growing from where it emanates from the stem. There is no incidence in which one peduncle arises from another peduncle, they always begin at a stem node and end at the base of the growing flower.

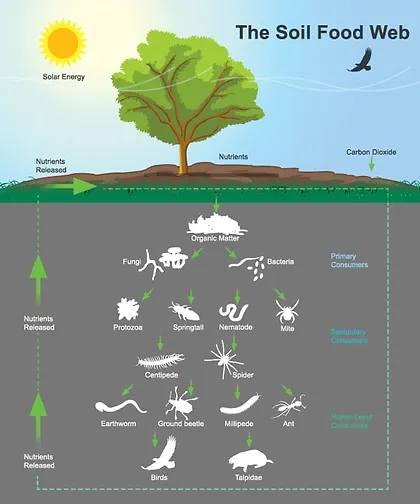

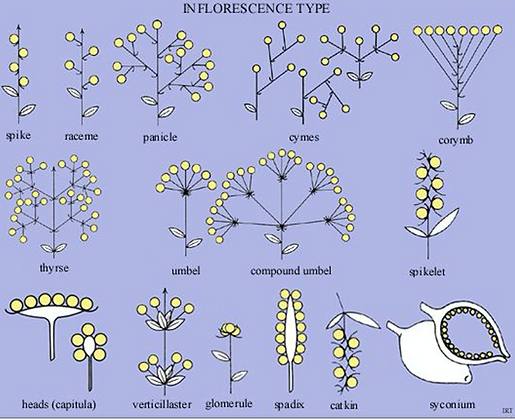

Plant Taxonomy is the science that finds, identifies, describes, classifies and names plants. Every part of the plant is examined in determining how to classify it. The reproductive parts are very important in the classification of plants overall. The way the flowers are arranged when they bloom is very important as well. In roses, the presentation of the flowers is very much at random. The vegetative tip produces a bud and then all sorts of different combinations can occur below the first bloom. In many plants the presentation of the blooms is not at random, but occurs in a specific way for any one variety of plant and the presentation is called an inflorescence. The names of most of the different types of inflorescences are probably not known to many, but there are a few that are familiar. Probably the most common would be the head. This is the type of flower presentation in plants such as sunflowers. There is one peduncle formed at the tip of the vegetative stem, just like in the rose, however that peduncle begins to divide and re-devide many times over. The stems that are produced by this division of the peduncle are called pedicels. In the case of the sunflower each of the pedicles produces a flower at its tip and they grow such that the structure that we know as a sunflower head is formed. In the representation to the left are many of the different ways that plants produce their flowers. In any one type of flower, sunflower for example, every time the vegetative stem becomes reproductive and produces a reproductive peduncle a head will be the result. The type of inflorescence formed by any one variety of plant will always be the same because it is in the genetics of the plant to grow that particular way. A rose may randomly produce a spray of blooms that resemble one of these classic inflorescence types, but it will not be a repeatable event. The occurrence will be strictly accidental since the genetics of the rose cause it to produce its flowers in the way previously described with each bloom arising from the stem of the plant on an individual peduncle.

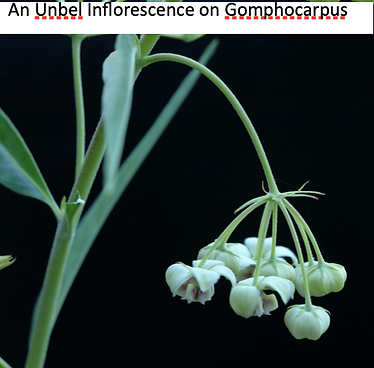

Another common type of inflorescence is the umbel. The peduncle that is produced branches into any number of different pedicles each having a flower at it tip. Probably one example known to gardeners would be either the carrot, or Queen Anne’s Lace. You can turn the flower over, the inflorescence, and see how the peduncle is divided over and over again producing the classic look of the Queen Anne’s Lace flower head. In each of examples in the diagram you will notice that the peduncle is emerging from the last leaf on the stem and then there are no leaves on it as it grows and divides.

As a botanist I observe what is going on in the garden at a little different level than the average gardener, which is not necessarily good or bad. But I think that the more you know about the things you enjoy, the more that you can enjoy them. I have a number of plants growing in pots that I am able to observe closely almost every day of their growing cycle, including one that has fascinated me for the last three years. When I first saw Asclepias physocarpa in a catalog, I knew I wanted to experiment in my garden with it. The taxonomist recently renamed it to Gomphocarpus physocarpus, but it is the same plant. It has many common names, including balloon flower, and family Jewels tree. But it is a member of the plants that Monarch butterflies feed on. I would like to see them in our part of Oregon. I have never seen one here in my over forty years of gardening here, but there is always hope. This plant produces flowers in an inflorescence known as an umbel, you can find it in the diagram of types. The peduncle originates from a node on the stem of the plant and grows and then it begins to divide into pedicels, normally with this plant there will be five to seven, each of which will bear one flower. I have nine of these plants growing around the yard, all of which are over 8 feet tall and there are literally thousands of blooms on them and every one of them is produced by exactly the same type of structure, the umbel. There is no randomness to all of the flowers, every one of the inflorescences looks exactly the same. So, you see that it certainly is not a random occurrence that the flowers are produced in umbels, the genetics of the plant makes every one of them the same. Going back to the rose, you might find five or six blooms that are presenting themselves such they look like they are an umbel, but it will certainly be random and will not repeat with any regularity and besides, each one of the blooms would be on its own peduncle.

The usage of the word inflorescence has become the dominant way that rose sprays are described in the judging guidelines for roses. I believe that the term is being misused and all collections of rose blooms on one stem should be referred to as sprays. In referring to the individual blooms of a spray the term floret is often used to describe them, and I believe that botanically this is incorrect as well. The word floret botanically refers to the tiny flowers of some grasses. It is correctly used for the flowers of cauliflower or broccoli or members of the compositae family like sunflowers.

WHAT COLOR IS THAT ROSE?, OH, NO COLOR!

Back when I worked for Edmund’s Roses when they were in Wilsonville, Oregon I got to talk to many people and try to answer their horticultural questions. One question often repeated was about rose colors. Is there a blue rose, or is there a black rose?

I could understand people wanting a blue rose because it is the only color that roses do not come in. However, black! If you had a black rose in the garden there would appear to be a hole in the bush where the flower was. Black items by nature do not reflect any light so you would not be able to see a truly black rose. Later I was honored to be part of the production of a book called “The Quest for the Black Rose” by Ingrid Verdeem around 2006 by describing many roses which were considered near black. It is still available used on e-bay for around $80. It was a giant of a book at the time measuring 17 inches by 13 inches and it does not fit anywhere on my bookshelves. I however I have a special place for it. A couple of the prominent and known roses to be discussed were Black Baccara by Meidiland, and Ain’t Misbehavin hybridized by Sean McCann.

When Sean’s rose was released around 1990 it was hailed as being very close to a black rose, but in reality it is consistently a very, very dark red. One of its parents was Black Jade, a long time favorite in our garden for being very dark red as a miniature. Last year when a planted rose seeds for the first time, one of the roses I took seeds from was Hoot Owl a Jerry Justice hybrid which is a medium red single miniature with a white eye. It was selected because it had an abundance of nice-looking hips when I pruned it in February. I was able to get a number of plants from the seeds of Hoot Owl which spanned the color spectrum from white to dark red, all of them singles. Because the plants were still small last fall, I moved a number of them into my garden shed where I continued to grow them under lights. What a surprise it was on the morning of January 21st, when I went out to water them to find a bloom on hoot 4 which gave me a thrill of seeing what I considered the first truly black rose I have ever seen. It was beautiful in its own way, but mostly for its uniqueness. This seedling had bloomed earlier during the summer outside and it very much resembled Ain’t Misbehavin when grown outside with a good dose of ultraviolet rays. But grown inside, it was a whole different rose. I do not think will bes, but it sure was fun seeing what I believed was a first black rose. Just as an aside, the picture was not underexposed to make it darker than it actually was, and you can tell that by the naturally colored green in the leaves.

Photos by Rich Baer