by Stephen Hoy

This article is a 2017 AOM winner

In August of 1854 eleven year old Robert Huey (January 15, 1843-March 12, 1928), along with parents Robert and Sophia Huey, emigrated from Ireland to Philadelphia, PA. In contrast to many fellow famine-devastated countrymen his family was financially stable. In 1858 he began his study of dentistry in nearby Lancaster, PA in the offices of Dr. John Waylan.

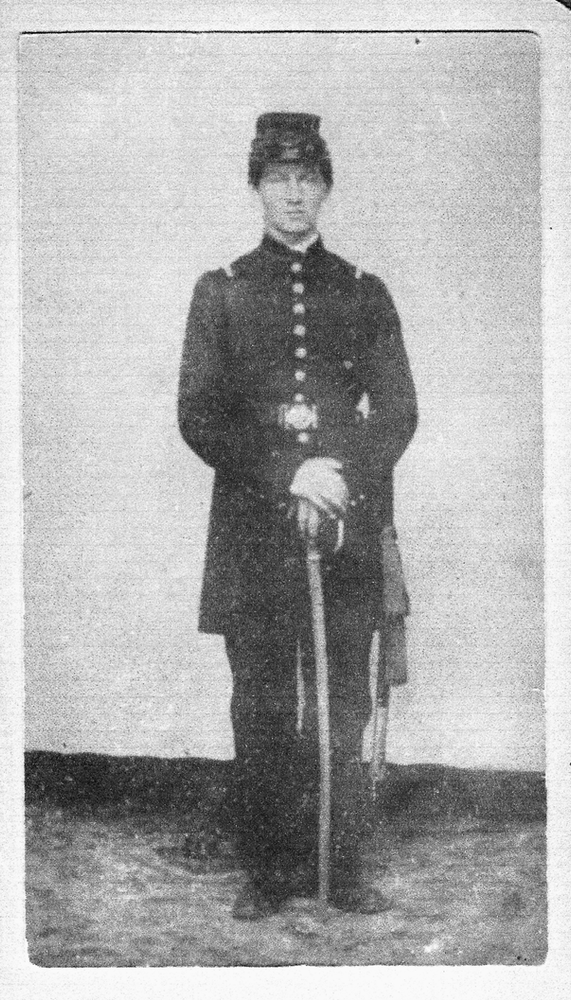

Just days after Confederate forces fired on federally occupied Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, young Huey responded to President Abraham Lincoln’s April 15, 1861 call for men to “maintain the Union.” He traveled to Camp Curtin in Harrisburg and enlisted in the 1st Pennsylvania Infantry, Company K, for a three month term of service. The regiment’s muster roll states that he was initially enrolled as a Musician, a practice that somewhat tacitly allowed regiments to accept boys and young men aged eighteen and under. Huey never actually became a member of the regimental band, but was assigned, rather, to commissary duty.

After being outfitted with muskets and cartridges, haversacks, and food provisions the regiment, under the command of Colonel Samuel Yohe, traveled south from Harrisburg by rail on April 20th. It was decided after arriving in Cockeysville, MD to return north to Camp Scott, near York, PA in order to refrain from provoking further unrest among the citizens of Maryland regarding the issue of secession.

After Union General Benjamin Butler occupied and declared martial law in Baltimore in the first weeks of May the 1st PA Infantry again traveled south to Maryland to guard the rail lines just outside the city of Baltimore. In the ensuing weeks the regiment was moved to various points to guard the roads and rail lines between Frederick and Baltimore. As part of a reorganization of Pennsylvania troops Huey’s regiment returned to Chambersburg, PA in early June. After assignment to General Patterson’s command the 1st PA Regiment returned to Maryland, guarding roads in the vicinity of Frederick. In early July the regiment was ordered west to Martinsburg to assume “garrison” duty. The First Battle of Bull Run or Manassas was just days away. On the very day of the first major battle of the Civil War, July 21, 1861, Robert Huey and the 1st PA received orders to move to Harper’s Ferry. Days later they boarded the train for Harrisburg, where they were mustered out July 27, 1861. It was said of the regiment that though it had not fought in any battles, “. . . its timely arrival in the field accomplished much good by checking any rash movement on the part of the Rebels in arms along our borders. The duties it was called on to perform were faithfully done, and its good conduct, under all circumstances, was appreciated and acknowledged by its superior officers.”

The men of Huey’s company returned to their homes in and around Lancaster. By mid-August, however, their captain, Henry A. Hambright, had sought and received authorization to raise a three-year regiment. In early September young Robert Huey, along with many members of the former company, joined the new unit, the 79th Pennsylvania Infantry.

By October 11, 1861 all the companies in the new regiment had reached full enrollment. They traveled to Harrisburg and then to Pittsburg, settling in Camp Wilkins under the command of Brig. General James S. Negley. During the unit’s stay in Pittsburg Huey was appointed the regiment’s Commissary-Sergeant. In late October they traveled by steamer down the Ohio River to Louisville, KY and from there, in December, to Munfordville, KY. Their duties so far primarily consisted of drilling and picket duty in the cold, rain, and mud of a southern winter.

On February 14, 1862 the 79th PA was ordered to reinforce General Ulysses S. Grant’s movement towards Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee, one that would eventually lead to the momentous battle at Shiloh. Fortunately for young Robert Huey, the order was soon countermanded and the regiment proceeded to Nashville, TN. During the ensuing months the unit traveled throughout Tennessee, guarding rail lines, repairing bridges destroyed by Confederate troops, and on occasion engaging enemy pickets.

Late in May General Negley’s brigade, then camped in Columbia, TN, was ordered east to assault Confederate forces entrenched in Chattanooga. After a victorious skirmish at Sweden’s Cove they reached the Tennessee capitol on June 6th and began shelling enemy troops. After two days of “brisk cannonading” Negley claimed victory and returned his command to Shelbyville, TN.

The 79th Pennsylvania would remain in Shelbyville for several months, celebrating the 4th of July there with parades and artillery salutes, enthusiastically encouraging pro-Union sentiment. Shortly thereafter they were sent southeast to Tullahoma where the regiment was reassigned to a new command under General William S. Smith. From there young Robert Huey and company were ordered back to Nashville to protect the region’s railroads and bridges.

In August plans were made for Union General Ambrose Burnside to advance into northeast Tennessee and drive Confederate forces out of Knoxville and the Cumberland Gap. Federal troops, including General James Shackelford’s newly organized 3rd Brigade (Cavalry), successfully occupied Knoxville on September 2nd. The brigade pursued retreating Confederate troops throughout the region with skirmishes occurring at Bull’s Gap, Carter’s Station, Zollicoffer, Blue Springs, and Blountville.

Their pursuit led them just above the Tennessee/Virginia border to Bristol.

Robert Huey’s skills as Commissary-Sergeant must have come to the attention of Colonel James P. T. Carter, commander of the 2nd East Tennessee Mounted Infantry (USA), one of the regiments assigned to Shackelford’s brigade. On September 13th, during the above mentioned campaign, Huey mustered out of the 79th PA and joined the staff of the 2nd TN as a lieutenant and Acting Assistant Adjutant-General of Commissary.

After the successful rout of Confederate troops at Bristol, the 2nd TN, the 7th Ohio Cavalry, and four guns from the 2nd Illinois Battery were detached from the 3rd Brigade on October 17th and sent to Rogersville, TN to establish an outpost intended to secure lines of communication. Lieutenant Huey records in his diary that after their arrival Colonel Carter was granted a thirty day leave of absence to visit his wife who was ill. Subsequently, Huey was ordered to “report for duty” to Colonel Israel Garrard, commander of the 7th OH.

Confederate forces led by General William “Grumble” Jones were alerted to the presence of the Union troops near Rogersville on November 3rd. According to an account written by the 7th Ohio’s Quarter-Master Sergeant, John L. Ransom, on the evening of November 5th, the “rebel citizens got up a dance at one of the public houses in the village and invited all the union [sic] officers.” Whether it was deliberate plot on the part of some of Rogersville’s southern sympathizers to distract Union leaders is unknown. The officer left in command of the 2nd TN was Major Daniel Carpenter. He reported being alerted to a Confederate movement in nearby Kingsport by Colonel Israel Garrard late in the day. The next morning Rebel troops began their attack. Sergeant Ransom stated that “Not one officer in five was present.” Confusion reigned. After several hours of fighting, Colonel Garrard and a significant percentage of the 7th OH “cut their way out.” Despite the efforts of Major Carpenter 608 of the 893 men of the 2nd TN were captured including young Lieutenant Robert Huey.

From Rogersville the prisoners were marched to Bristol, VA. From there they boarded boxcars and traveled by train to Richmond. Huey and twenty-two commissioned officers from his regiment were imprisoned in Libby Prison on November 12th; the enlisted men were taken to Belle Isle in Richmond’s James River. During the ensuing winter months the conditions were brutal. Lack of food, freezing temperatures, severe overcrowding, and infestations of lice made life miserable for the officers who were at least quartered inside a brick building. Although tents and blankets were provided for a percentage of the enlisted men imprisoned on Belle Isle, a greater number were forced to survive with no shelter whatsoever.

Increasing Union military pressure on the Confederate capitol prompted the Confederate government to consider moving Richmond’s prison population further south. In mid-January of 1864 construction began on a stockade near a small rail depot in Sumter County, Georgia. Named Fort Sumter by Confederate authorities, the horrors that would occur in what would become known as Andersonville give voice to the capabilities of human animosity.

Two events occurring in February further augmented the urgency to transfer Union prisoners out of Richmond. On the 9th 159 men (not including Huey) escaped from Libby through a sixty foot tunnel. Although many were recaptured a sense of alarm gripped the city. In response, the first trainload of prisoners from Belle Isle was sent to still-under-construction Fort Sumter. Several days later Union General Judson Kilpatrick, aided by Colonel Ulric Dahlgren, led a failed raid on Richmond. Its civilian population, unnerved and panic-stricken, demanded further action. By late March Belle Isle was emptied, the living having been transported from one hell to another. Remaining in Richmond, however, were over 1000 Union officers.

By late April Confederate authorities faced a dilemma at Andersonville. Although intended to be a prison for enlisted and political prisoners 110 officers arrived among a large group of POW’s (captured near Plymouth, NC) on the 30th. Commander of the Georgia Reserves, General Howell Cobb, reminded the commander of the prison Captain Henry Wirz that a facility named Camp Oglethorpe in nearby Macon, GA had served as a stockade two years earlier. The next day the officers were transported the sixty plus miles north to Macon. Confederate Inspector General Samuel Cooper made it official on May 2nd instructing Cobb to “Make proper provisions for the safe keeping of Federal officers to be sent from Andersonville to Macon, Georgia.”

The door was now open to also remove the remaining Union prisoners from Richmond. On May 7th the commissioned officers housed in Libby Prison, including Lieutenant Robert Huey, were loaded on trains and sent southward. After pausing at the stockade in Danville, VA the train continued southward to Macon.

On the morning of the 17th twenty-four carloads of wretched-looking men arrived at Camp Oglethorpe. A two-week veteran of the camp, Chaplain Henry White of the 5th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, was shocked by their appearance. He wrote, “A new class of suffering was before me. The men were old [long-term] prisoners, and pale and haggard. They were ragged, and some partly naked. They were filthy, and covered with vermin.”

Twenty-one year old Robert Huey lived there among a group that would eventually number roughly 1400 on a plot of ground about the size of two and a half football fields. The higher ranking officers slept inside the one enclosed building still standing from the stockade’s former days as a fairground. A few dozen men slept under the building, some in roofed wooden structures without floors or walls; many slept under the stars. Cooking pots and utensils were limited and shared by all. Three small barrel-sized wells provided drinking water for everyone inside the stockade walls. Food consisted primarily of maggot-infested bacon and un-sifted corn flour, although some vegetables could be purchased by those that had the means to barter.

As in many other Civil War era prisons the men fought despair and tedium in numerous ways at Camp Oglethorpe. Sunday preaching and mid-week prayer meetings led by captured Union minister-soldiers sustained many. One prisoner noted the formation of a literary society made possible by the purchase of a library of books and magazines from a Macon citizen desperate to raise some cash. Card games, baseball games, classes in foreign languages, and evening social gatherings occupied some. Tunneling, as a means of escape, was another dedicated enterprise. In his “Reminiscences” Huey noted that he enthusiastically joined in the effort, digging every other night for three weeks. On the 4th of July the prisoners celebrated with patriotic speeches and rousing patriotic songs.

Let no one think that these pursuits made life easy for the men imprisoned at Camp Oglethorpe. Scurvy and debilitating dysentery ravaged hundreds and killed some. A prisoner from Wisconsin wrote, “To fall ill was vile, to stay well a miracle.” Those unfortunate to have been wounded prior to arriving in the central Georgia stockade received little in the way of medical care. Almost all were afflicted with infestations of lice. The seeming lack of concern for their condition as prisoners on the part of the Federal government, the rarity of news from family members, exposure to the extremes of weather, lack of food, and the emotional baggage of being a prisoner in a hostile environment was devastating. A lieutenant from my home town of Mechanicsburg, PA made a note in his diary, “Tired, weary of nothing to do. The continual wandering of the mind into vague reverie, until it becomes a burden to itself, is wearisome in the extreme.”

General William Sherman’s successful advance on Atlanta prompted Confederate leaders to contemplate moving the prisoners out of Macon in late July. On July 27th, just as one of Sherman’s cavalry leaders, General George Stoneman, began his southerly raid to free his captured Union comrades, the first of two groups of roughly 600 men were loaded on trains headed to Charleston, SC. Approximately twenty-four hours later the second group departed. Lieutenant Huey was among the first 600 to leave Macon. After arriving in Charleston they were confined in the city jail yard until an outbreak of yellow fever forced many, including young Huey, to be relocated to the nearby U.S. Marine hospital.

On October 5th the severity of the yellow fever outbreak and the controversial use of human shields by both sides in the ongoing bombardment of Charleston led to the transfer of Federal prisoners to Camp Sorghum in Columbia, SC. After dark on the 6th Lieutenant Huey and Lieutenant James C. McDonald (also of the 2nd TN), jumped from their train transport just north of Orangeburg, SC and made their escape. They traveled through swamp and dense woods frequently relying of the good will of slaves to provide food and direction. After several days they decided to “take the main stock road through Newberry and Greenville to North Carolina.”

After arriving in the vicinity of Laurens, SC Huey and McDonald inadvertently revealed their presence to a local via the smoke of a campfire. A pack of dogs was raised and the pair was chased down, recaptured, and temporarily confined in the Laurens Court House on October 18th. Shortly thereafter, they were sent back to Camp Sorghum.

In the SC stockade it was routine for sentries to allow small groups of prisoners to step outside the guard line to collect firewood. In just over two weeks Huey recognized an opportunity to once again escape. Late in the afternoon of November 4th he “noticed that the officer of the guard was very careless with paroled squads, in fact that he was a little “loose,’ or “tight” as some people call it . . . He allowed the paroled prisoners to pass the lines without counting them.” Lieutenant Huey, unable to find his previous accomplice McDonald, grabbed another messmate, Lieutenant J. C. Martin (1st East Tennessee Artillery), and calmly joined a squad headed out to collect firewood. As they hid themselves in the woods several other prisoners joined them.

During the ensuing weeks Huey and company made their way through the South Carolina countryside. The threat of being recaptured kept them cautious about revealing their presence or when in need of directions. Once again the benevolent assistance of the slave population played a significant role in their journey.

By the 22nd of November the band reached the Chattooga River, the dividing line between northwest South Carolina and northeast Georgia. After successfully passing themselves off to locals as Confederate soldiers on furlough they were ferried across the river and continued their journey. After crossing into North Carolina Huey and company began to encounter Union sympathizers who kindly provided food and shelter and pointed them toward other “loyal” families along their way. Huey recorded, “We are getting so robust and hearty with the abundance of nourishing food that we think nothing of the exertion of our marches; during the first days after our escape every mile was an exertion, but now, our only trouble is our feet. I am the worst off in this particular being practically barefoot and limp along with difficulty; if only I had a good pair of shoes.”

Their travels took them almost due west across the Little Tennessee and Nantahala Rivers toward the head waters of the Hiawassee River. Union sympathizing NC soldiers, home on furlough, provided guidance across the mountainous terrain; several asked to accompany Huey in his attempt to reach Federal lines.

On December 4th they crossed into Tennessee near the Ducktown copper mines and headed toward the home of retired Union General James Gamble on the banks of the Ocoee River. From there the company traveled northwest to Charleston, TN, the nearest Union outpost, arriving on the 6th. By his estimate, Huey and his fellow prison escapees had traveled 387 miles more or less barefoot and in the same clothes worn when captured thirteen months earlier.

Because of their haggard appearance the group was immediately arrested and detained, suspected as Rebel spies. When questioned by the officer in charge Huey requested permission to communicate with Union General Samuel P. Carter headquartered in nearby Knoxville in order to confirm his identity. Within an hour Carter joyously replied and provided train transport to Knoxville for Huey and his companions – three Union officers and five civilians. The small company took the first train to Knoxville where they were celebrated as heroes. Lieutenant Huey was made an aid to General Carter and his fellow escapees were granted leaves of absence. In his new position Huey signed certificates of loyalty for his North Carolina friends and found them employment.

Robert Huey ends his reminiscences with a sobering post script likely added some years later. “Of the four hundred ninety-four Officers and enlisted men of the 2nd East Tenn. Mounted Infantry regiment captured at Rogersville, Tenn. Three hundred and eighty-two died from disease and starvation in Rebel prisons. Had I not escaped there would probably have been three hundred and eighty-three.”

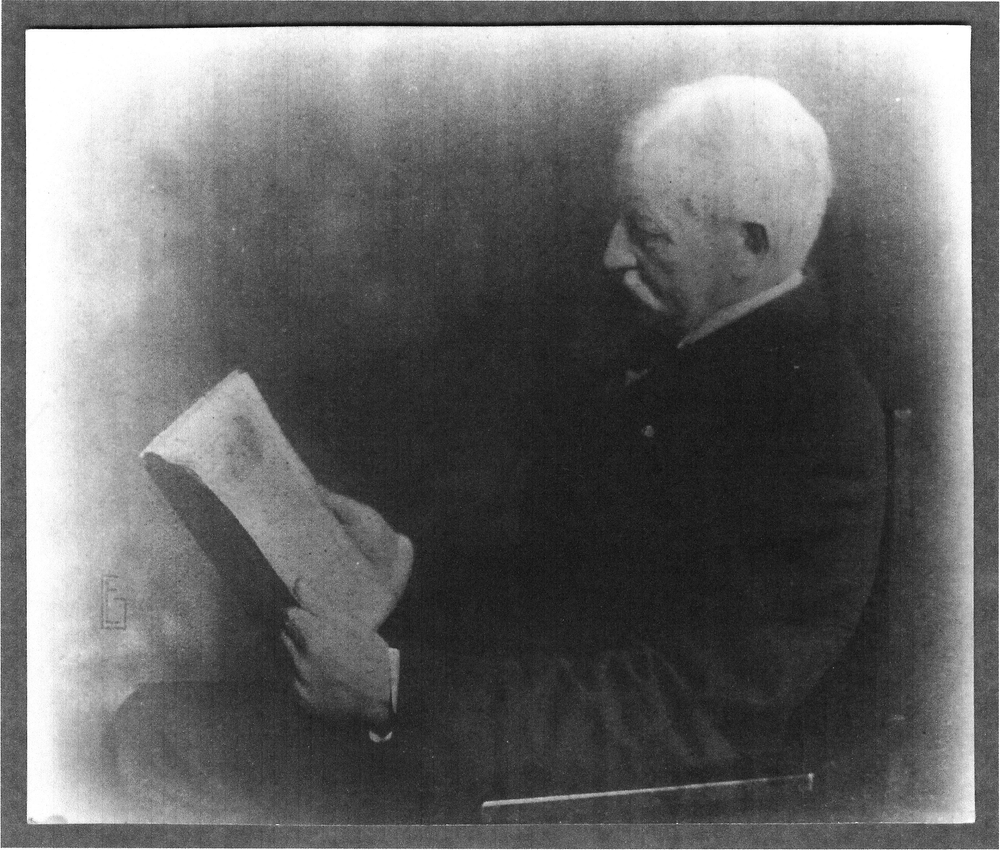

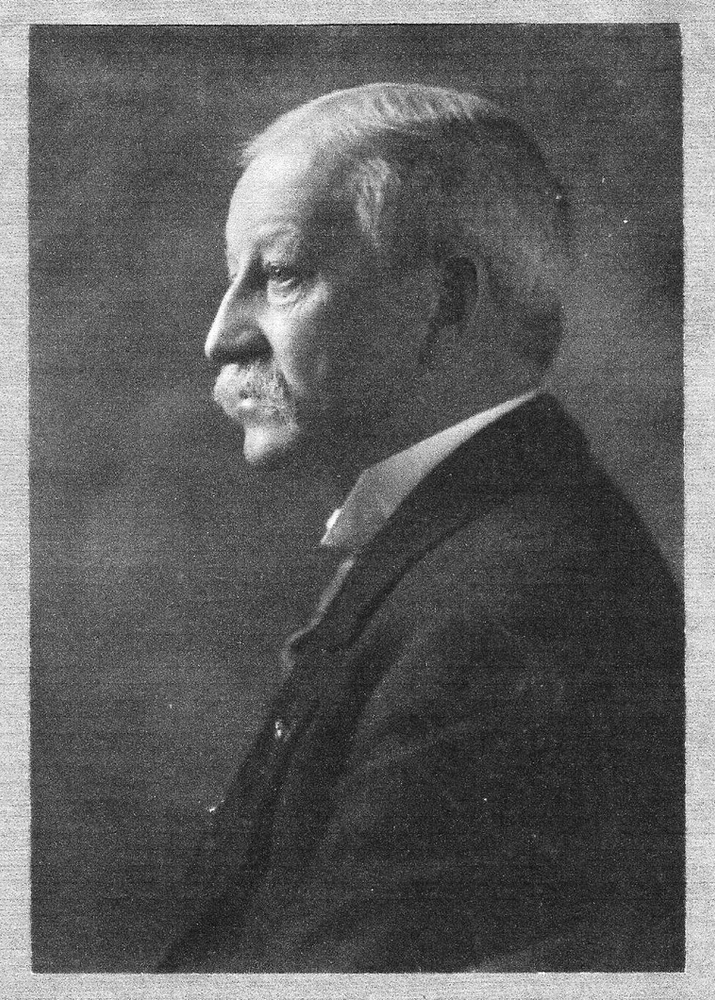

A return to civilian life began for Robert Huey when he was honorably mustered out on January 14, 1865, one day before his twenty-second birthday. He returned to the study of dentistry, graduating from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery in March of 1867. Dr. Robert Huey married Katharine [Catherine] C. Goepp on December 28, 1874; the couple had five children, two boys and three daughters (Robert Jr., Alice Katharine, Helen, Clifford Carr, and Katharine). His family life was tragically marred by the death of his wife in 1885, his youngest son in 1887, and his oldest son in 1896.

Perhaps because of these tragedies Dr. Robert Huey filled his life with numerous activities and affiliations. He was well-known as a pioneer and lecturer in the field of dental surgery while a member of the faculty at the newly formed School of Dental Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He served in various positions with the Pennsylvania Board of Dental Examiners and the Pennsylvania Association of Dental Surgeons. Outside his vocation Dr. Huey served as president of the English Setter Club of America and was involved in promoting and participating in dog shows and field days. He grew fond of another outdoor activity as well, one he pursued with characteristic Huey enthusiasm – growing roses.

A record of Huey’s interest in roses appears in correspondence shared with J. Horace McFarland, editor of the American Rose Annual.

“My earliest rose recollection is of an attempt to pluck a moss rose in my grandmother’s garden and of getting my fingers pricked by the sharp thorns. Rescued by the nurse, the thorns were removed, and I was turned loose in the belief that a lesson had been taught. Nevertheless, I wanted that rose, and returned to the attack with a like result. Mother then appeared on the scene, took in the situation, cut the rose, removed the thorns, and made me happy with the flower. I have loved roses ever since.” n

[Editor’s Note: from the mention of a nurse it may be reasonably postulated that the incident occurred before Huey’s immigration to America at age eleven. His heritage as a son of Ireland explains his future patronage of the Irish rose-growing firm Alexander Dickson & Sons.]

Editor McFarland further quoted Huey:

. . . After being established in [dental] practice upon my return [from the war], and feeling the need for outdoor relaxation, I purchased a home and two acres of ground in 1877, and began to try to grow roses. There was then little reliable information to be had, and the flowers that resulted compared most unfavorably with illustrations in the catalogues, while the plants would die by the dozen. Persevering, I finally met with success, and knowing that many others were thirsting for knowledge I began writing and talking of my experiences and how my difficulties were overcome, thus doing a sort of rose missionary work.

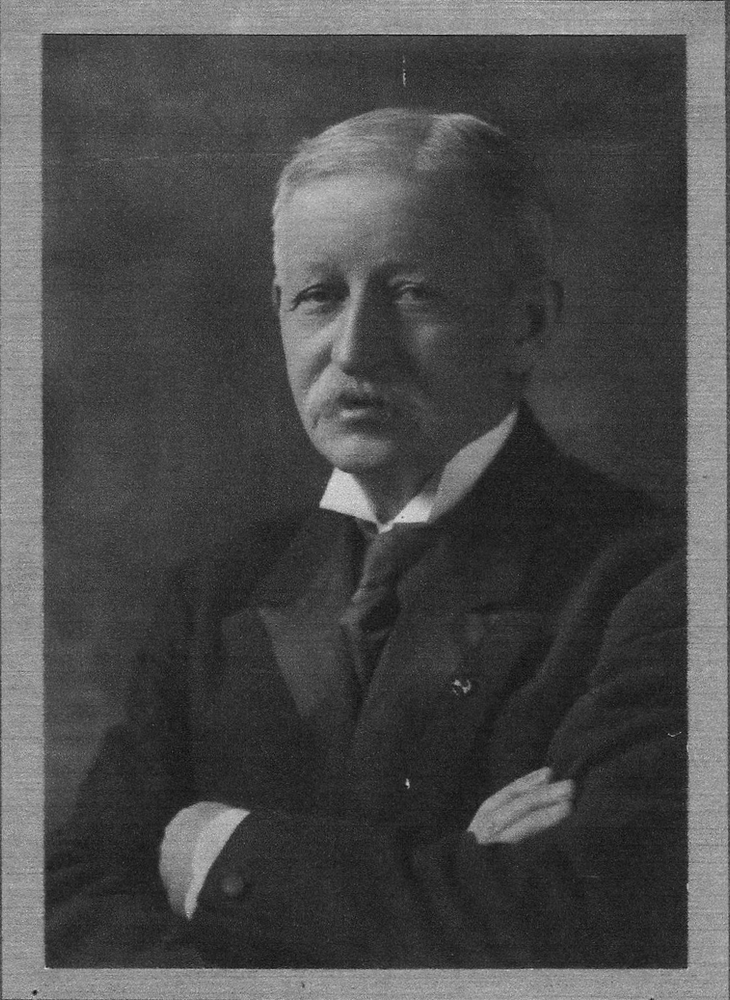

Among those “converted” by Huey’s missionary efforts was a young banker from a prominent Philadelphia family, George C. Thomas, Jr. Between the two substantial contributions to successful outdoor rose culture were made with unique emphasis placed on the advantages of grafted/budded roses and on the suitability/adaptability of specific rose cultivars and classes for the diverse climatic conditions found across the United States.

The initial work was begun by Huey the mentor. In 1896 the June edition of The American Florist reported a lecture given by the doctor to the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society entitled “Outdoor Roses,” drawing special attention to his “experience with a great variety of roses.” Leonard Barron noted in his book Roses and How to Grow Them that Dr. Huey had by that time [1905] thoroughly tested every Hybrid Perpetual in the Dickson & Sons catalog. He also invested noteworthy effort in evaluating the relatively new group of roses classified as Hybrid Teas. Due to his close association with Alexander B. Scott, American agent for A. Dickson & Sons, Huey was one of the first American rose enthusiasts to grow the newly introduced ‘Killarney.’ In an article appearing in the March, 1905 issue of the periodical Country Life in America, Huey noted that he had observed a decided advantage in budded plants of ‘Ulrich Brunner’ when compared to a bed of “strong own-root” plants of the same variety. In a grand moment of irony, he advised, “It is very probable that the best stock for our use has not yet been introduced . . .” Although Rosa multiflora became the rootstock of choice for many growers another choice would unknowingly be created by Huey’s most ambitious understudy.

After being gifted with fifty rose bushes from Dr. Huey in 1901 George C. Thomas, Jr. set about breeding roses in 1912 with a goal of producing everblooming climbing roses and better garden varieties. His first introductions were hybridized at the family’s Bloomfield Farm. In 1914 a dark red once-blooming seedling resulted from a cross of ‘Ethel,’ a light pink Hybrid Wichuraiana, and the scarlet ‘Gruss an Teplitz,’ a vigorous Hybrid Tea. It and several other seedlings were sent to the Rutherford, New Jersey nursery firm Bobbink & Atkins for evaluation where their commercial introduction was delayed for several years by the commencement of the First World War.

Meanwhile Robert Huey’s influence as an American authority on growing roses continued to broaden. He was well-known by many of the movers and shakers associated with the ARS, including Robert Pyle, president of the Conard-Jones Company. The 1916 edition of Pyle’s How to Grow Roses contains a section dedicated to Huey’s recommended varieties for “Philadelphia and Vicinity.”

That same year Dr. Huey was present at the annual meeting of the officers of the American Rose Society in Philadelphia. ARS President S. S. Pennock recognized him as “one of the best amateur rose-growers in this country” and invited him to address the group. Huey praised the society for the publication of its first Rose Annual (1916) and proposed that the ARS direct its focus more toward the general public rather than commercial growers. He further recommended the creation of a committee that could provide information and answer questions regarding rose culture (the eventual formation of that committee would lead to the creation of the Consulting Rosarian Program).

Additionally, during the meeting President Pennock read a letter written by George C. Thomas, Jr. suggesting that a system of point-scoring be adopted to more accurately assess the “outdoor” merit of new rose introductions. Originated by Thomas, Dr. Huey, and Portland, Oregon rosarian Jesse A. Currey the system was to be implemented in the new wave of test-gardens being created throughout the United States [Of interest to the author is the creation of a standard definition for single-flowered roses – “A single rose shall be one which has from four to ten petals . . .”].

Huey’s interest in the pros and cons of budded plants prompted him to write an article entitled “Propagation by Budding,” published in the 1917 American Rose Annual. Forty years of growing roses had convinced him that buddedrose bushes, in particular Hybrid Perpetuals, Teas, and Hybrid Teas, were superior to own-root roses in growth and development. In addition to ‘Manetti,’ and seedling Brier (R. canina), he specifically recommended Rosa multiflora for roses grown in the Philadelphia region and gave detailed, illustrated instructions on “how-to.”

At the spring 1917 annual meeting of the ARS a resolution was passed to increase the size of the executive committee. Along with the Rev. E. M. Mills, J. Horace McFarland, W. G. McKendrick, and Dr. Huey were elected as Honorary Vice-Presidents of the American Rose Society, “the object being to elect representatives from amateur membership, who, by their interest, would tend to increase the membership of the Society.

Shortly after this meeting America joined its allies France, Great Britain, and Russia (April 6, 1917) and declared war on Germany. George C. Thomas, Jr., an amateur aviator, volunteered to join the war effort. After a period of training and outfitting, his squadron left for Europe where he would fly a number of bombing missions.

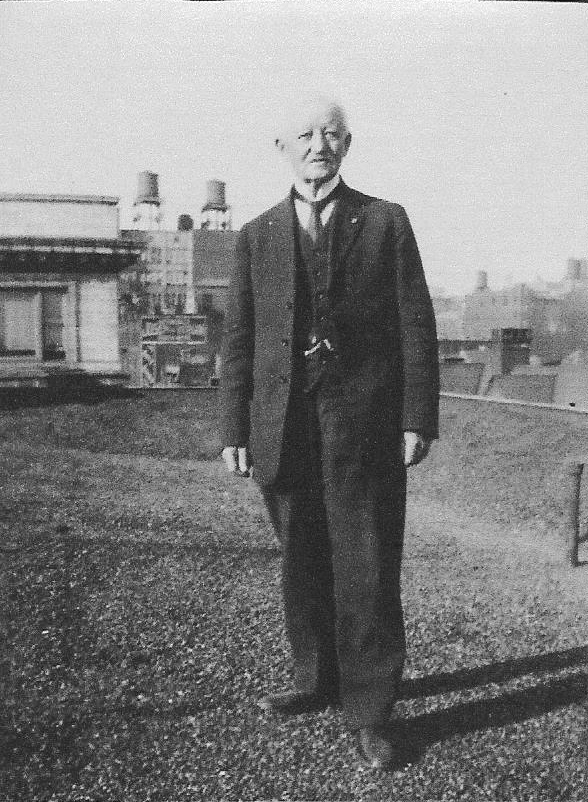

In January of 1918 Dr. Huey was appointed to fill a vacancy in the Rose Test-Garden Committee, filling a void created by the death of Admiral Aaron Ward. Later that year Dr. Robert Huey’s garden was requisitioned as part of a land grab associated with the expansion of Philadelphia’s Hog Island shipyard – part of America’s massive endeavor to put more naval vessels into the war effort. The ongoing work of Captain George C. Thomas, Jr. would become the megaphone giving voice to the accumulated experience and knowledge of the now elderly doctor.

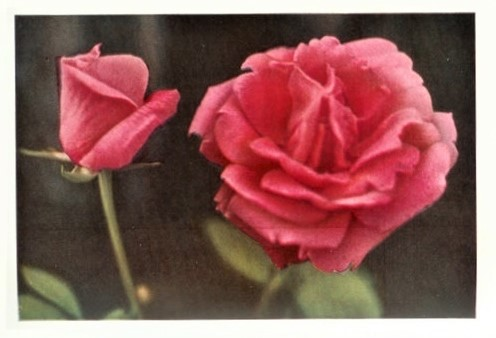

Early in 1919, now “Captain” Thomas returned to his home in Philadelphia. On June 4th of that year he and his wife entertained the executive committee of the American Rose Society in their Bloomfield garden. During the meeting Thomas dedicated seedling number 720, the aforementioned dark red hybrid to his mentor Dr. Robert Huey. He recorded some personal comments about the rose in the 1920 edition of his book, The Practical Book of Outdoor Rose Growing, “It has been our good fortune to breed a crimson maroon climber which Dr. Robert Huey has chosen from among our seedlings to bear his name. The rose is a very dark color and blooms most profusely during its season. It is semi-double and retains its petals and color for a long period, besides being of vigorous growth.” Although the rose, named ‘Dr. Huey,’ did not meet Thomas’ repeat-flowering breeding goal, he believed it possessed enough individuality to merit introduction

Huey, despite the loss of his garden, continued his rose missionary work locally – preaching the gospel of good growing practices. At a meeting of Philadelphia’s New Century Club in December of 1922 Huey delivered a lecture that has been recorded for posterity. Entitled “The Cultivation of Out-Door Roses,” seventy-nine year old Dr. Huey outlined a regimen of practical strategies that could pass for the latest in how-to: a situation with plenty of circulation, away from invasive tree roots, staggered planting, well-drained, loosened, weed-free soil, regular fertilization, mulch, appropriate pruning based on knowledge of the growing habits of the cultivar, protection from winter frosts, removal of diseased foliage, thorough irrigation, and CHOOSING SUITABLE CULTIVARS!

Dr. Huey had been a member of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society since 1905, serving as Vice-President from 1917-1918. In recognition of his pioneering work with roses he was honored with the society’s Gold Medal in November of 1924.

The last years of soldier, dentist, dog-lover, and venerated rosarian, Dr. Robert Huey, were lived in relative peace and quiet. He lived on Spruce Street with his unmarried sister-in-law Eleanor Goepp. On March 12, 1928 Dr. Robert Huey died at his home of heart failure at eighty-five years of age. He was buried in nearby West Laurel Hill Cemetery beside his wife and sons. An obituary appearing in The Dental Cosmos read,

“As a practitioner of dentistry the service of Dr. Huey both to his clientele and to his profession was the reflex of his character as a man: conscientious, sympathetic, a lover of humanity, he gave of the best that was in him, gave it cheerfully and abundantly. His loyalty to any cause that enlisted his cooperation was unflinching and enthusiastic. His war record, his cooperation in dental society work, his helpfulness in the many social and special activities that engaged his interest, testify to the conscientious thoroughness which characterized all his undertakings.

It is said with much truth that “all the world loves a lover” and the underlying thought has a general as well as a special application. Dr. Huey was a lover in the larger meaning of that term. He loved his friends and in that category may be fairly included not only his human relationships but all living things “both great and small” that came within the wide circle of his life interests. It was that quality, the sincere and sympathetic regard in which he held all who won a place in his friendship that endeared him to them. His friendship was a benediction and a benefaction that will endure throughout the lives who knew him.”